Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NYOctober 25—December 21, 2019

The heavy dark falls back to earthAnd the freed air goes wild with light,The heart fills with fresh, bright breathAnd thoughts stir to give birth to colour.– Matins, John O’Donohue

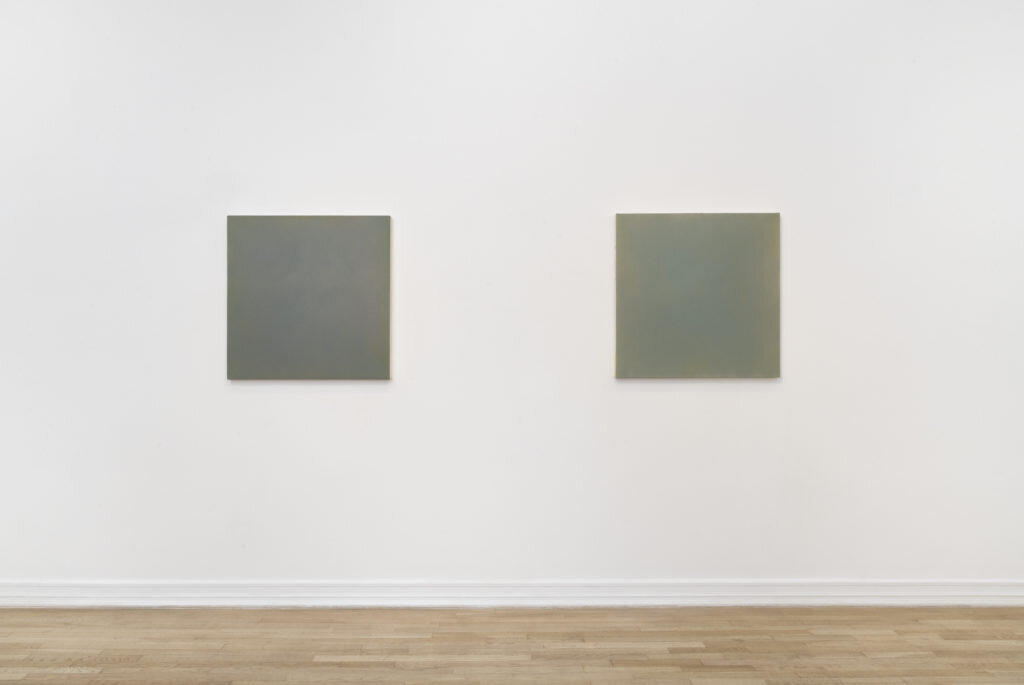

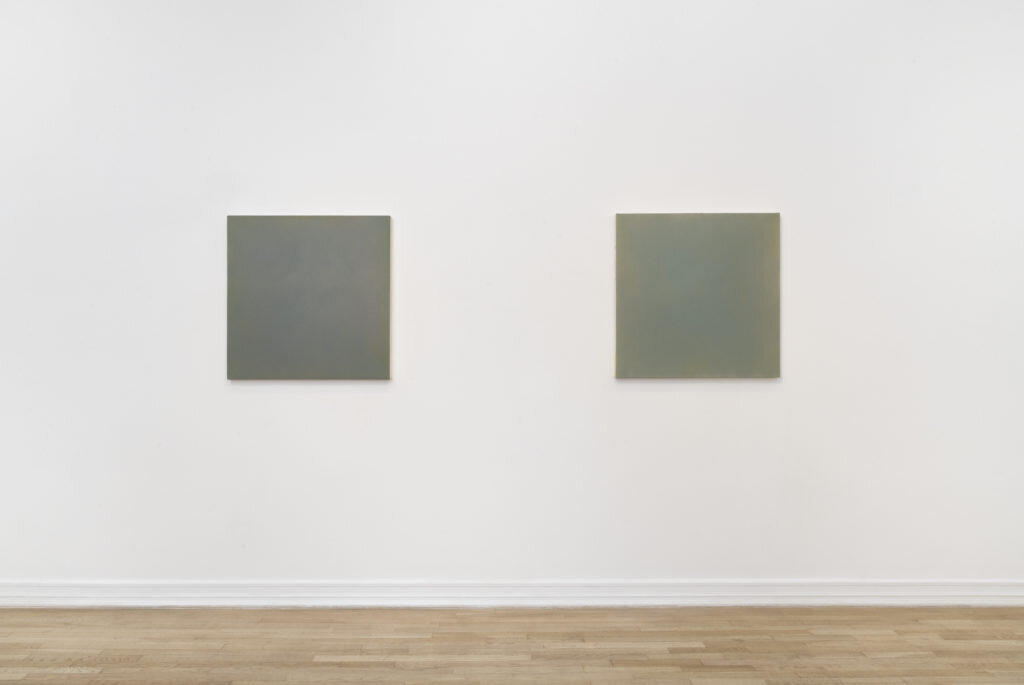

Franklin Parrasch Gallery is pleased to announce its first exhibition of Jefferson City, Montana-based painter Anne Appleby. The show, entitled Hymn: First Light, Last Light, consists of eight works from the artist’s most recent series. Observing and responding to her secluded wilderness surroundings, Appleby distills her own perceptions of natural elements as they perpetually alter throughout their life cycles.

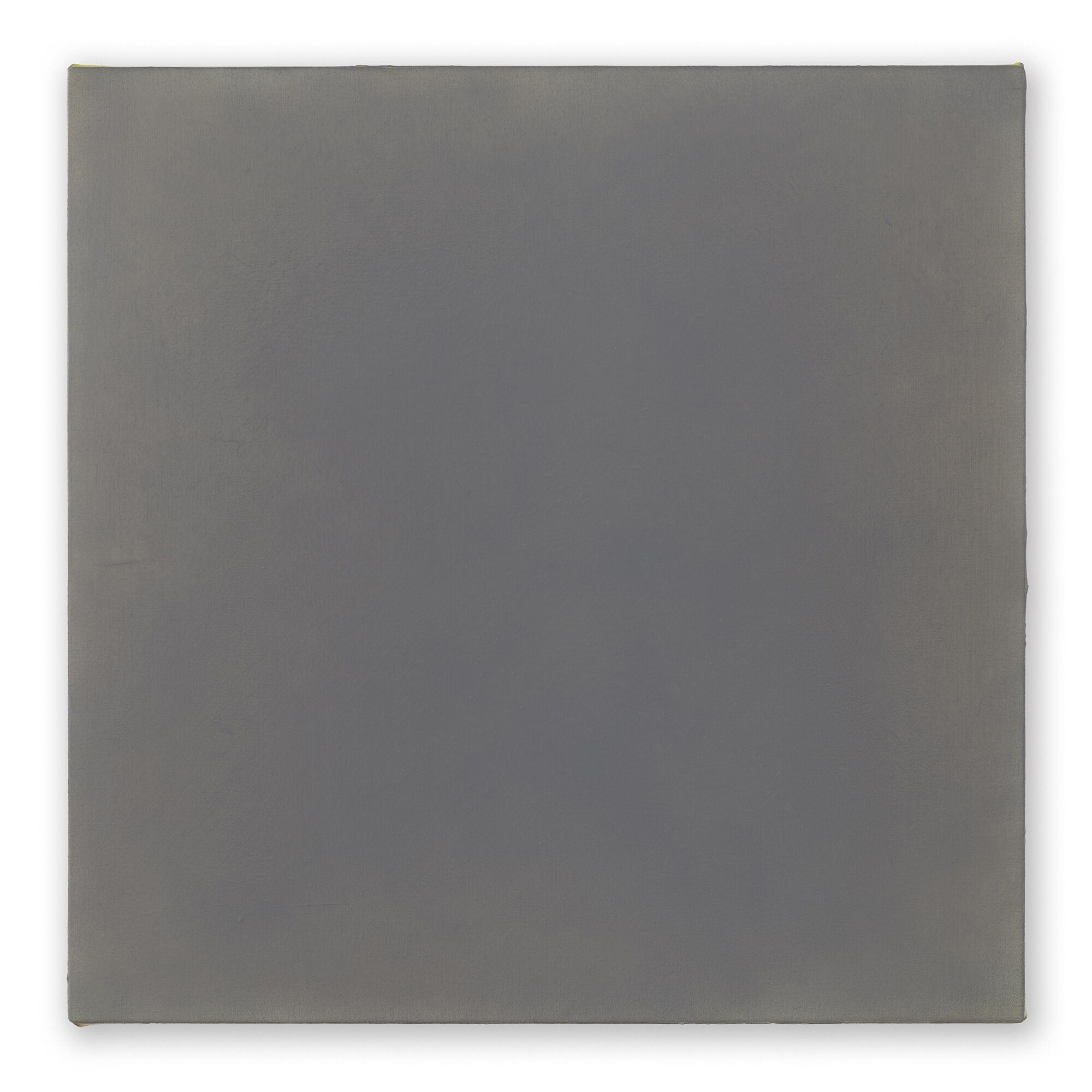

Acknowledging the activity of constant transition and impermanence in the natural world, Appleby articulates an impression of the quality of light (or lack thereof) in pre-dawn and post-dusk states. Reflecting upon an Ojibwa belief that certain souls wander in a pre-color state before they wander into the light, Appleby intuits the metaphorical impact of such a journey in these paintings, each of which depicts shifting tonal densities of grey built through numerous subtly visible chromatic layers. Exploring the mystery of chromatic perception, the artist’s surfaces, which often consist of up to 50 layers of oil and wax mediums, resonate with variation and depth.

As noted by Emily Stamey, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at Wichita State University’s Ulrich Museum of Art:

“Appleby’s holistic attention to her physiological and psychological experiences in nature plays an equally important role in her process. Rather than work only empirically from what she sees, the artist allows subjective remembered experiences in the landscape to guide her. She describes the approach as “interior,” a practice that acknowledges her very personal relationship to nature.”

Born in Harrisburg, PA in 1954, Appleby studied at Philadelphia College of Art before relocating to Montana in 1971, subsequently earning her BFA at the University of Montana, Missoula, and eventually establishing a studio and residence in the sparsely populated community of Jefferson City. In addition to receiving her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1989, Appleby’s educational background includes a fifteen-year apprenticeship with Ojibwa artist and holy man Ed Barbeau, with whom she learned and refined processes of intense meditative awareness in nature. The tenor of Appleby’s work reflects the sensation of that observational practice and resides at the core of her philosophical approach to painting.

Appleby’s work has been exhibited in numerous solo exhibitions at galleries and museums worldwide, including Mayor Gallery, London (2010); Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco (1993-2011); Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese (2007); and Borzo Gallery, Amsterdam (2016). Her works are held in the permanent collections of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (Buffalo, NY), Daimler Art Collection (Stuttgart/Berlin, DE), Denver Museum of Art (CO), Microsoft Corporation (Redmond, WA), National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC), the Panza Collection (Lugano, CH), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (CA), and the Seattle Art Museum (WA), amongst others. A solo exhibition titled A Hymn for the Mother will take place in 2020 at the Missoula Art Museum (MT).

Hymn: First Light, Last Light will be on view at Franklin Parrasch Gallery, 53 East 64th Street, New York, NY, from October 25—December 21, 2019. For images, biography, and further information, please contact the gallery at info@franklinparrasch.com or at 212-246-5360 during business hours: 10a-6p, Tuesday-Saturday.

by John Yau, November 9, 2019

Hyperallergic.com

I want to begin with two quotes. The first is from the press release for Anne Appleby’s current exhibition, Anne Appleby: Hymn: First Light, Last Light, at Franklin Parrasch Gallery:

In addition to receiving her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1989, Appleby’s educational background includes a fifteen-year apprenticeship with Ojibwa artist and holy man Ed Barbeau, with whom she learned and refined processes of intense meditative awareness in nature.

The second is from a Seattle Times review by Robin Updike (November 12, 1998):

Appleby […] has some Native American ancestry in her family tree […].

Identity is not always cut and dry. Together, these two statements convey some of complexity that can result when one’s lineage is not — to use a term reserved for dogs and the Aryan-minded — purebred.

I want to establish this cultural context for Appleby’s paintings because she is a monochromatic artist, but she is not a purist. In this, her debut show at the Upper East Side gallery Franklin Parrasch, she showed 8 square paintings, all 30 by 30 inches, which is about the physical area one sees when staring straight ahead. Again, I think the press release is helpful:

Reflecting upon an Ojibwa belief that certain souls wander in a pre-color state before they wander into the light, Appleby intuits the metaphorical impact of such a journey in these paintings, each of which depicts shifting tonal densities of grey built through numerous subtly visible chromatic layers.

When I began looking at the eight paintings, which were displayed on three different walls (two groups of two and one group of four), I forgot that the press release underscored the importance of “gray.” I saw other muted tones, inflected by green, but I did not see gray.

It took a while for me to adjust to what I was looking at — a monochromatic painting where the central area often, but not always, distinguishes itself from the rest of the painting in both texture and hue. Let me be clear: this is not say there is a form in the center; there is more of an atmospheric change, a feeling of condensation. The paintings are both monochromatic and tonal. Their subject is not color but imminent light or darkness, that period of limbo.

Standing alone in the quiet, high-ceilinged room, I was reminded of the first stanza of Robert Creeley’s poem “The Door (II)”:

It is hard going to the door

cut so small in the wall where

the vision which echoes loneliness

brings a scent of wild flowers in a wood.

Four of the eight paintings have “First Light” in their title and the other four have “Last Light.” Appleby gives further clues to her inspiration by including a parenthetical descriptor with each painting, as in “Last Light (August)” (2019). Yet, I think it is a mistake to try and nail down a connection between painting’s title and the experience of looking at it.

Appleby, who lives on a ranch in rural Montana, is highly attuned to the colors she sees in her landscape, as well as to the changing light and seasons. As much as her paintings are rooted in these, they are not based on direct observation. However, in bringing up her biographical details, I am proposing that Appleby’s monochromatic paintings are not about color, but about nature and light.

I would go further and say that her paintings don’t emerge solely from Western art — either the optical lineage that begins with Claude Monet and Georges Seurat and passes through Josef Albers to the present, or the reductive lineage that originates with Kazimir Malevich and is redefined by Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, and others. Clearly, her long apprenticeship with an Ojibwa artist and holy man taught her to look at the natural world differently than either of these two diverse groups. The one modern artist in these lineages she has a clear affinity to is Agnes Martin. Like Martin, Appleby lives in a largely uninhabited landscape dominated by nature, where one becomes conscious of the sky’s presence, its constantly changing conditions. At the same time — and this speaks to the landscape’s affect on the artist — Appleby’s work looks nothing like Martin’s.

What Appleby’s paintings ask you to do is lose yourself, enter the interior space that can come with looking, but, in these content-driven times, seldom does. In “Last Light (August),” I felt as if I was trying to look into a dense fog, to discern what was form and what was light, unable to fix on any part of the painting. The effect is disconcerting because Appleby conjures an in-between state, where nothing attains definition, nor is anything completely dispersed.

Rather than seeing a form or a field, I found my focus readjusting as I tried to see into the painting — their layered surfaces certainly invite the viewer to do that. The colors evoke nature but not in any nameable way; the sense of a wet dawn or evening glow shrouded in mist is perhaps the strongest.

What to me is most disconcerting about these paintings — but also contributes deeply to the pleasure in experiencing them — is that I began to feel bodiless, like a ghost, when I looked at them. They didn’t mirror me; rather, I felt as though I were beginning to mirror them. I could begin to enter the painting through my eyes — and they certainly pulled me into their miasma. Yet for various reasons, including their size, I felt I could not physically enter them.

As Creeley writes in “The Door (II),” “the vision which echoes loneliness.” This is the metaphor that, for me, came through the paintings. Whatever journey we are on, there are periods when we have no idea where we are going, what we are about, or what we are supposed to do. We do not want to believe that we live in limbo, but perhaps we should.

For in not knowing where we are when looking at these paintings, we might want to consider where it is we want to go and, more importantly, how will we get there with regards to the natural world.